About Dyslexia

What is Dyslexia?

- Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.

- Adopted by the IDA Board of Directors, Nov. 12, 2002. Many state education codes, including New Jersey, Ohio and Utah, have adopted this definition. Learn more about how consensus was reached on this definition: Definition Consensus Project.

Dyslexia Description

- Reading is complex. It requires our brains to connect letters to sounds, put those sounds in the right order, and pull the words together into sentences and paragraphs we can read and comprehend.

- People with dyslexia have trouble matching the letters they see on the page with the sounds those letters and combinations of letters make. When they have trouble with that step, all the other steps are harder.

- Dyslexic children and adults struggle to read fluently, spell words correctly, and learn a second language. But these difficulties have no connection to their overall intelligence. In fact, dyslexia is an unexpected difficulty in reading in an individual who has the intelligence to be a much better reader. While people with dyslexia are slow readers, they often, paradoxically, are very fast and creative thinkers with strong reasoning abilities.

- Dyslexia is very common. It affects 20 percent of the population and represents 80– 90 percent of learning disabilities.

- Scientific research shows differences in brain connectivity between dyslexic and typical reading children, providing a neurological basis for why reading fluently is a struggle for those with dyslexia.

- Dyslexia can’t be “cured” – it is lifelong. But with the right supports, dyslexic individuals can become highly successful students and adults.

Characteristics of Dyslexia

The Preschool Years

- Delayed spoken language

- Trouble learning songs and nursery rhymes

- Difficulty learning (and remembering) names of letters

- Mispronounces familiar words; persistent “baby talk”

- Doesn’t recognize letters in own name

- Unable to create or recognize rhyming patterns like cat, bat, rat

- Family history of reading and/or spelling difficulties (dyslexia often runs in families)

Elementary, Middle & High School

Reading

- Slow in acquiring reading skills

- Reading errors that show no connections to letter sounds, such as “kitty” instead of “cat” when there is a picture of a cat

- Little awareness of sounds in words, sound order, rhymes, or sequence of syllables

- Reading is slow and labored

- Lacks a strategy for reading new words, often guesses based on first or last letters

- Problems with reading comprehension

- Complains about how hard reading is; makes excuses to avoid it

- History of reading problems in parents, siblings, or extended family

Spelling and Writing

- Repeated spelling errors

- Studies for a spelling test but cannot retain the words the following week

- Difficulty expressing thoughts in written form despite creative ideas or strong understanding of topic

- Handwriting that is slow, messy, or awkward

Speech

- Has trouble expressing thoughts orally

- Difficulty in finding the “right” word; searches for a specific word and ends up using vague language, such as “stuff” or “thing”

- Pauses, hesitates, and/or uses lots of “um’s” when speaking

- Confuses words that sound alike, such as saying “tornado” for “volcano,” substituting “lotion” for “ocean”

- Imprecise or incomplete interpretation of language that is heard

Math

- Difficulties in mathematical calculations

- Reading word problems is challenging

- Cannot memorize simple things like basic math facts, addresses, and phone numbers

- May have dyscalculia

- Struggles to extend patterns or sequences

Life Skills

- Struggles with low self-esteem, anxiety, embarrassment

- Uncertain as to right- or left-handedness; confuses left and right

- Difficulty with organization

- Confusion about directions in space or time (up & down, months & days, etc.)

- Took a long time to learn to tie shoes or can’t yet

- Dislike or avoids school

Young Adult And Adult

Reading

- Childhood history of reading and spelling difficulties

Reading requires great effort despite improvement over time - Rarely reads for pleasure

- Reads most materials slowly and inaccurately

- Avoids reading aloud

Speaking

- Uses a lot of “um’s” and imprecise language

- Is anxious when speaking

- Pronounces names and places incorrectly

- Confuses words that sound alike

- Trips over parts of words

- Struggles to retrieve words

- Responds slowly in conversations

- Uses smaller vocabulary when speaking than when listening

- Avoids words that may be mispronounced

School & Life

- Struggles taking tests

- Penalized for spelling errors

- Sacrifices social life for studying

- Fatigues easily when studying or reading

- Performs rote clerical tasks poorly

- Concerned that peers think they’re dumb

- Has poor self-esteem, shame

Dyslexia Strengths

- Embraces new ideas

- Curiosity and imagination

- Understanding of new concepts

- Comprehension of stories read or told to them

- Understands “big picture”; gets gist of things

- Creative problem solving; thinks outside the box

- Critical thinking

- Success in areas not dependent on reading

- Improvement if given additional time

- Writing skills, if spelling isn’t counted

- Success in areas not dependent on rote memory

- Empathy and warmth

- Hard workers

What Dyslexia is Not...

- NOT caused by laziness; dyslexics work hard, often with poor results

- NOT seeing or reading backward; dyslexia is unrelated to vision

- NOT caused by a lack of focus; attention difficulties may be present, but are not the cause

- NOT a disease, so it has no cure; its effects can be diminished with Structured Literacy Instruction and accommodations.

- NOT a result of low intelligence; it is a difficulty with language skills, not thinking

- NOT related to poverty or lack of education; it occurs across all income and educational levels

- NOT caused by social/emotional difficulties; frustration from failing to learn basic skills may cause emotional problems

- Dyslexia is not caused by laziness or lack of effort; dyslexics work as hard or harder than non-dyslexic peers, often with worse results

- Dyslexia is not seeing or reading backward; dyslexia is unrelated to vision

- Dyslexia is not caused by a lack of focus; ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) may be present, but is not the cause

- Dyslexia is not a disease, so it has no cure; its effects can be diminished with Structured Literacy Instruction

- Dyslexia is not a result of low intelligence; it is a difficulty with language skills, not thinking skills

- Dyslexia is not caused by poverty or lack of educational opportunity

- Dyslexia is not caused by laziness, inattention, poor vision, low intelligence, or social/emotional problems. However, the frustration of failing to learn basic skills can cause emotional problems

- ADHD (Attention deficit hyperactive disorder) may be present, but it does not cause dyslexia

- It is a myth that individuals with dyslexia read or see “backward”; dyslexia is not a vision problem

- The difficulty with reading and spelling is not because they are not trying hard enough

- Dyslexia is not a disease, and therefore there is no cure

- Individuals with dyslexia do not have a lower level of intelligence

Dyslexia Strengths

The Michigan Dyslexia Handbook is designed to help educators and district and school leaders develop a shared understanding of best practices to prevent reading difficulties associated with the primary consequences of dyslexia (word-level reading disability) and to implement assessment practices needed to inform the instruction and intervention methods for learners with dyslexia characteristics.

Structured Literacy And Dyslexia

What is Structured Literacy?

At IDA we believe that teaching practices must be grounded in scientific, peer-reviewed research. Structured Literacy is an evidence-based instructional approach that emphasizes all components of literacy. This includes foundational skills such as decoding and spelling, and higher-level skills such as reading comprehension and written expression. It also focuses on oral language skills including phonemic awareness, sensitivity to speech sounds, and the the ability to manipulate those sounds. This approach is effective for all children learning to read, but is essential for those with dyslexia or anyone who experiences unusual difficulty learning to read and spell.

Key Elements of Structured Literacy

The most difficult problem for students with dyslexia is learning to read. Unfortunately, popularly employed reading approaches, such as Guided Reading or Balanced Literacy, are not effective for struggling readers. These approaches are especially ineffective for students with dyslexia because they do not focus on the decoding skills these students need to succeed in reading.

What does work is Structured Literacy, which prepares students to decode words in an explicit and systematic manner. This approach not only helps students with dyslexia. There is substantial evidence that it is more effective for all readers. Continue reading for a description of each component of Structured Literacy.

Phonology

Phonology is the study of the sound structure of spoken words. Phonemic Awareness, an essential element of Structured Literacy, is the ability to identify and manipulate individual sounds (phonemes) in spoken words. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound that can be recognized as being distinct from other sounds in the language. Activities that promote phonemic awareness include rhyming, tapping phonemes, clapping syllables, and deleting or changing sounds.Strong phonemic awareness is a good predictor of reading success.

Sound-Symbol Association

Sound-Symbol Association, often called phonics, is the ability to identify a letter name and symbol(s) with a specific phoneme or sound. It must be taught and mastered in two directions: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to visual (spelling). Students must master the blending of sounds and letters into words and the segmenting of whole words into individual sounds.

Syllable Instruction

A syllable is a unit of language with one vowel sound. By knowing the syllable type, the reader can determine the sound of the vowel in the syllable. Syllable division rules allow readers to decode long, unfamiliar words by chunking them into smaller pieces. The six syllable types are:

- Closed: spelled with a single vowel ending in one or more consonants. Vowel sound is short. Examples: kid, candle

- Open: ends with a long vowel sound spelled with a single vowel letter. Examples: we, begin

- Vowel-Consonant-e (Silent e): spelled with one vowel + one consonant + silent e. Examples: line, exhale

- Vowel Team: includes 2-4 letters representing a long, short, or dipthong vowel sound. Examples: spoil, auto, trainer

- Vowel-R: syllable with er, ir, or, ar, or ur. Vowel pronunciation often changes before /r/. Examples: fur, car, perform, further

- Consonant-le: unaccented final syllable that contains a consonant before /l/, followed by a silent e. Examples: little, bundle

Morphology

A morpheme is the smallest unit of meaning in the language. The Structured Literacy curriculum includes the study of base words, roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The word instructor, for example, contains the root struct, which means to build or teach, the prefix in, which means in or into, and the suffix or, which means one who. An instructor is one who builds knowledge in their students.

Syntax

Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the sequence and function of words in a sentence. This includes grammar, sentence structure, language mechanics, and punctuation. Syntax delinieates a specific order for grammatical elements like subjects, verbs, and direct objects. Consider the following sentences:

- She enjoys cooking her family and her dog.

- She enjoys cooking, her family, and her dog.

One type of syntax error is incorrect comma usage, which can affect meaning.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of words, sentences and phrases and their meaning. Many words have similar meanings and it is important to distinguish their subtle differences. For example, “anger” and “rage” are similar in meaning, but “rage” implies a stronger reaction.

Instructional Methods for Structured Literacy

Systematic and Cumulative

Structured Literacy instruction is systematic and cumulative. Systematic means that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic concepts and elements and progress methodically to more difficult concepts and elements. Cumulative means each step must be based on concepts previously learned.

Explicit Instruction

Structured Literacy instruction requires the deliberate teaching of all concepts with continuous student-teacher interaction. It is not assumed that students will naturally deduce these concepts on their own.

Diagnostic Teaching

The teacher must be adept at individualized instruction. The instruction is based on careful and continuous assessment, both informally (e.g., observation) and formally (e.g., standardized tests). The content presented must be mastered to the degree of automaticity. When students decode words automatically, it allows them attend to comprehension and fluency.

Balanced Literacy vs Structured Literacy

What is Balanced Literacy?

At MI-IDA our goal is for every classroom in the state to use literacy instruction proven by research to be effective at teaching all students to read and write. Sadly, literacy testing suggests this is not the case. As reported by Michigan.gov, Michigan is facing a literacy crisis. As of 2017, 64% of fourth graders were at or below basic reading levels and just 27% were proficient readers.

Adapted from https://iowareadingresearch.org/blog/structured-and-balanced-literacy

A crucial cause of this crisis is the use of Balanced Literacy, an approach focusing on activities that surround children with quality literature and promote a love of reading. While this is an admirable goal, Balanced Literacy lacks the explicit, systematic, sequential instruction required for accurate decoding.

Balanced Literacy and Structured Literacy

This chart highlights the key differences between Balanced and Structured Literacy.

Structured Literacy

Phonics skills taught explicitly and systematically, with

prerequisite skills taught first.

Parts to whole phonics approach: students learn letter sounds and patterns and how to blend them.

Beginning readers read decodable texts, which are controlled to specific phonics patterns that have been explicitly taught. This allows students use phonics skills in books.

Oral text reading with a teacher is included in lessons.

When reading orally, students encouraged to to apply decoding skills such as letter sounds and syllabication when reading unfamiliar words.

Spelling skills taught explicitly and systematically with prerequisite skills taught first. Instruction reinforces reading skills.

Higher levels of literacy such as sentence structure and paragraph writing are explicitly and systematically taught.

Balanced Literacy

Phonics taught but not emphasized. Teaching may not be explicit or systematic.

Phonics approach may be synthetic, but is often whole to parts with less examination of sounds and patterns.

Beginning readers usually read leveled and predictable texts, in which words can be guessed based on sentence structure, repetition, or pictures. Text not controlled for phonics skills previously learned.

Partner and independent reading often emphasized more than oral reading.

When students read orally, errors not affecting meaning may be overlooked. Error correction may emphasize sentence context or pictures rather than spelling and pronunciation.

Spelling often not taught explicitly or systematically. Words may not exemplify particular phonics patterns or rules. Spelling program may not reinforce reading program.

Higher literacy skills may be explicitly taught but

often not systematically or with attention to prerequisite skills.

Why is Balanced Literacy Ineffective?

- It is not supported by peer-reviewed, scientific research. Research has shown that exposure to unfamiliar words wtihout appropriate decoding instruction will lead to use of compensatory strategies, such as relying on picttures. Creating cozy reading areas and giving kids books by award-winning authors is wonderful, but ineffective if they aren’t receiving comprehensive in how to read.

- It promotes guessing. One of the pillars of Balanced Literacy is the three-cueing system, which encourage students students to conjecture words using semantic, syntactic, and visual cues. Here is an example:

- In the sentence, “My favorite farm animal is a donkey,” the student struggles to read “donkey.”

- The teacher asks questions such as

- What animals start with d?

- Would “dog” make sense in this sentence?

- Is “dog” always a farm animal?

- What animal do you see in the picture?

- Student says “donkey,” but is not reading it using letter sounds and syllable patterns, and won’t be able to read it in isolation.

- Multiple studies have proven that skilled readers rely primarily on a word’s spelling and pronunciation rather than syntactic and semantic cues, yet it is still widely used. This came from https://www.readingrockets.org/content/pdfs/structured-literacy.pdf

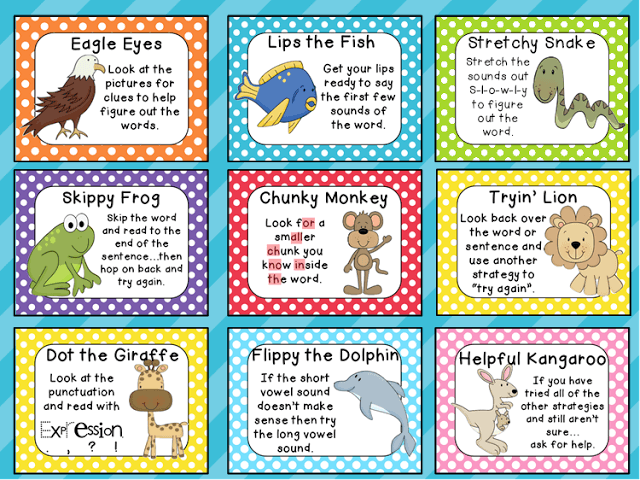

- The chart blow highlights some of the “strategies” promoted by Balanced Literacy. Note that “Lips the Fish” and “Chunky Monkey” are the only two that encourage use of letter-sound correspondence, but are only used for part of the word.

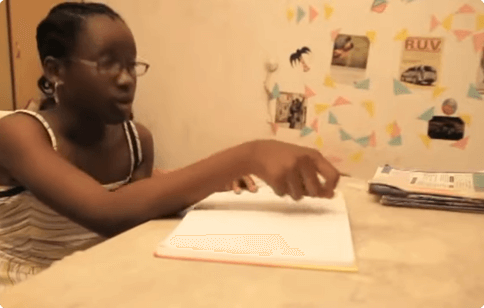

Is My Kid Learning How To Read?

In the following videos, parent and behavioral scientist Esti Iturralde conducts experiments with her first grader to show that phonics instruction, not Balanced Literacy, leads to strong decoding skills.

Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong

It is not supported by peer-reviewed, scientific research. Research has shown that exposure to unfamiliar words wtihout appropriate decoding instruction will lead to use of compensatory strategies, such as relying on picttures. Creating cozy reading areas and giving kids books by award-winning authors is wonderful, but ineffective if they aren’t receiving comprehensive in how to read.